[Click here for a PDF of this post with nicer formatting]

Motivation.

Chapter V notes for [1].

Notes

Problems

Problem 1.

Statement.

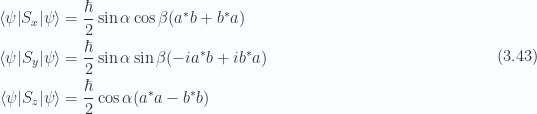

Obtain  for spin 1 in the representation in which

for spin 1 in the representation in which  and

and  are diagonal.

are diagonal.

Solution.

For spin 1, we have

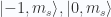

and are interested in the states  . If, like angular momentum, we assume that we have for

. If, like angular momentum, we assume that we have for

and introduce a column matrix representations for the kets as follows

then we have, by inspection

Note that, like the Pauli matrices, and unlike angular momentum, the spin states  have not been considered. Do those have any physical interpretation?

have not been considered. Do those have any physical interpretation?

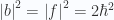

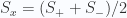

That question aside, we can proceed as in the text, utilizing the ladder operator commutators

to determine the values of  and

and  indirectly. We find

indirectly. We find

![\begin{aligned}\left[{S_{+}},{S_{-}}\right] &= 2 \hbar S_z \\ \left[{S_{+}},{S_{z}}\right] &= -\hbar S_{+} \\ \left[{S_{-}},{S_{z}}\right] &= \hbar S_{-}.\end{aligned} \hspace{\stretch{1}}(3.8)](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cbegin%7Baligned%7D%5Cleft%5B%7BS_%7B%2B%7D%7D%2C%7BS_%7B-%7D%7D%5Cright%5D+%26%3D+2+%5Chbar+S_z+%5C%5C+%5Cleft%5B%7BS_%7B%2B%7D%7D%2C%7BS_%7Bz%7D%7D%5Cright%5D+%26%3D+-%5Chbar+S_%7B%2B%7D+%5C%5C+%5Cleft%5B%7BS_%7B-%7D%7D%2C%7BS_%7Bz%7D%7D%5Cright%5D+%26%3D+%5Chbar+S_%7B-%7D.%5Cend%7Baligned%7D+%5Chspace%7B%5Cstretch%7B1%7D%7D%283.8%29&bg=fafcff&fg=2a2a2a&s=0&c=20201002)

Let

Looking for equality between ![\left[{S_{z}},{S_{+}}\right]/\hbar = S_{+}](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cleft%5B%7BS_%7Bz%7D%7D%2C%7BS_%7B%2B%7D%7D%5Cright%5D%2F%5Chbar+%3D+S_%7B%2B%7D&bg=fafcff&fg=2a2a2a&s=0&c=20201002) , we find

, we find

so we must have

Furthermore, from ![\left[{S_{+}},{S_{-}}\right] = 2 \hbar S_z](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cleft%5B%7BS_%7B%2B%7D%7D%2C%7BS_%7B-%7D%7D%5Cright%5D+%3D+2+%5Chbar+S_z&bg=fafcff&fg=2a2a2a&s=0&c=20201002) , we find

, we find

We must have  . We could probably pick any

. We could probably pick any

, and

, and  , but assuming we have no reason for a non-zero phase we try

, but assuming we have no reason for a non-zero phase we try

Putting all the pieces back together, with  , and

, and  , we finally have

, we finally have

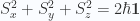

A quick calculation verifies that we have  , as expected.

, as expected.

Problem 2.

Statement.

Obtain eigensolution for operator  . Call the eigenstates

. Call the eigenstates  and

and  , and determine the probabilities that they will correspond to

, and determine the probabilities that they will correspond to  .

.

Solution.

The first part is straight forward, and we have

Taking  we get

we get

with eigenvectors proportional to

The normalization constant is  . Now we can call these

. Now we can call these  , and

, and  but what does the last part of the question mean? What’s meant by

but what does the last part of the question mean? What’s meant by  ?

?

Asking the prof about this, he says:

“I think it means that the result of a measurement of the x component of spin is  . This corresponds to the eigenvalue of

. This corresponds to the eigenvalue of  being

being  . The spin operator

. The spin operator  has eigenvalue

has eigenvalue  ”.

”.

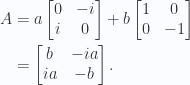

Aside: Question to consider later. Is is significant that  ?

?

So, how do we translate this into a mathematical statement?

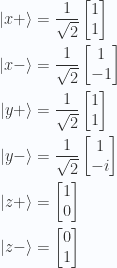

First let’s recall a couple of details. Recall that the x spin operator has the matrix representation

This has eigenvalues  , with eigenstates

, with eigenstates  . At the point when the x component spin is observed to be

. At the point when the x component spin is observed to be  , the state of the system was then

, the state of the system was then

Let’s look at the ways that this state can be formed as linear combinations of our states  , and

, and  . That is

. That is

or

Letting  , this is

, this is

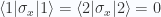

We can solve the  and

and  with Cramer’s rule, yielding

with Cramer’s rule, yielding

or

It is  and

and  that are probabilities, and after a bit of algebra we find that those are

that are probabilities, and after a bit of algebra we find that those are

so if the x spin of the system is measured as  , we have a $50\

, we have a $50\

Is that what the question was asking? I think that I’ve actually got it backwards. I think that the question was asking for the probability of finding state  (measuring a spin 1 value for

(measuring a spin 1 value for  ) given the state

) given the state  or

or  .

.

So, suppose that we have

or (considering both cases simultaneously),

or

Unsurprisingly, this mirrors the previous scenario and we find that we have a probability  of measuring a spin 1 value for

of measuring a spin 1 value for  when the state of the operator

when the state of the operator  has been measured as

has been measured as  (ie: in the states

(ie: in the states  , or

, or  respectively).

respectively).

No measurement of the operator  gives a biased prediction of the state of the state

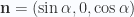

gives a biased prediction of the state of the state  . Loosely, this seems to justify calling these operators orthogonal. This is consistent with the geometrical antisymmetric nature of the spin components where we have

. Loosely, this seems to justify calling these operators orthogonal. This is consistent with the geometrical antisymmetric nature of the spin components where we have  , just like two orthogonal vectors under the Clifford product.

, just like two orthogonal vectors under the Clifford product.

Problem 3.

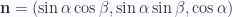

Statement.

Obtain the expectation values of  for the case of a spin

for the case of a spin  particle with the spin pointed in the direction of a vector with azimuthal angle

particle with the spin pointed in the direction of a vector with azimuthal angle  and polar angle

and polar angle  .

.

Solution.

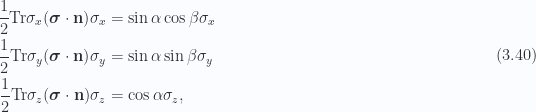

Let’s work with  instead of

instead of  to eliminate the

to eliminate the  factors. Before considering the expectation values in the arbitrary spin orientation, let’s consider just the expectation values for

factors. Before considering the expectation values in the arbitrary spin orientation, let’s consider just the expectation values for  . Introducing a matrix representation (assumed normalized) for a reference state

. Introducing a matrix representation (assumed normalized) for a reference state

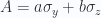

we find

Each of these expectation values are real as expected due to the Hermitian nature of  . We also find that

. We also find that

So a vector formed with the expectation values as components is a unit vector. This doesn’t seem too unexpected from the section on the projection operators in the text where it was stated that  , where

, where  was a unit vector, and this seems similar. Let’s now consider the arbitrarily oriented spin vector

was a unit vector, and this seems similar. Let’s now consider the arbitrarily oriented spin vector  , and look at its expectation value.

, and look at its expectation value.

With  as the the rotated image of

as the the rotated image of  by an azimuthal angle

by an azimuthal angle  , and polar angle

, and polar angle  , we have

, we have

that is

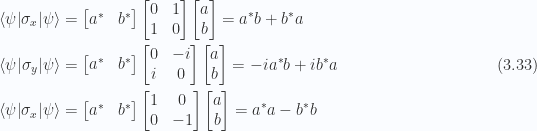

The  projections of this operator

projections of this operator

are just the Pauli matrices scaled by the components of

so our  expectation values are by inspection

expectation values are by inspection

Is this correct? While  is a unit norm operator, we find that the expectation values of the coordinates of

is a unit norm operator, we find that the expectation values of the coordinates of  cannot be viewed as the coordinates of a unit vector. Let’s consider a specific case, with

cannot be viewed as the coordinates of a unit vector. Let’s consider a specific case, with  , where the spin is oriented in the

, where the spin is oriented in the  plane. That gives us

plane. That gives us

so the expectation values of  are

are

Given this is seems reasonable that from 3.43 we find

(since we don’t have any reason to believe that in general  is true).

is true).

The most general statement we can make about these expectation values (an average observed value for the measurement of the operator) is that

with equality for specific states and orientations only.

Problem 4.

Statement.

Take the azimuthal angle,  , so that the spin is in the

, so that the spin is in the

x-z plane at an angle  with respect to the z-axis, and the unit vector is

with respect to the z-axis, and the unit vector is  . Write

. Write

for this case. Show that the probability that it is in the spin-up state in the direction  with respect to the z-axis is

with respect to the z-axis is

Also obtain the expectation value of  with respect to the state

with respect to the state  .

.

Solution.

For this orientation we have

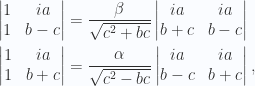

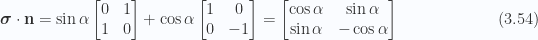

Confirmation that our eigenvalues are  is simple, and our eigenstates for the

is simple, and our eigenstates for the  eigenvalue is found to be

eigenvalue is found to be

This last has unit norm, so we can write

If the state has been measured to be

then the probability of a second measurement obtaining  is

is

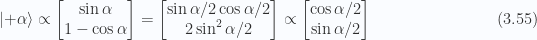

Expanding just the inner product first we have

So our probability of measuring spin up state  given the state was known to have been in spin up state

given the state was known to have been in spin up state  is

is

Finally, the expectation value for  with respect to

with respect to  is

is

Sanity checking this we observe that we have  as desired for the

as desired for the  case.

case.

Problem 5.

Statement.

Consider an arbitrary density matrix,  , for a spin

, for a spin  system. Express each matrix element in terms of the ensemble averages

system. Express each matrix element in terms of the ensemble averages ![[S_i]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5BS_i%5D&bg=fafcff&fg=2a2a2a&s=0&c=20201002) where

where  .

.

Solution.

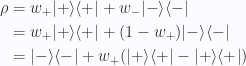

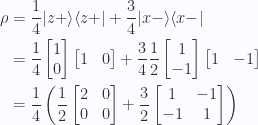

Let’s omit the spin direction temporarily and write for the density matrix

For the ensemble average (no sum over repeated indexes) we have

![\begin{aligned}[S] = \left\langle{{S}}\right\rangle_{av} &= w_{+} {\langle {+} \rvert} S {\lvert {+} \rangle} +w_{-} {\langle {-} \rvert} S {\lvert {-} \rangle} \\ &= \frac{\hbar}{2}( w_{+} -w_{-} ) \\ &= \frac{\hbar}{2}( w_{+} -(1 - w_{+}) ) \\ &= \hbar w_{+} - \frac{1}{{2}}\end{aligned}](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cbegin%7Baligned%7D%5BS%5D+%3D+%5Cleft%5Clangle%7B%7BS%7D%7D%5Cright%5Crangle_%7Bav%7D+%26%3D+w_%7B%2B%7D+%7B%5Clangle+%7B%2B%7D+%5Crvert%7D+S+%7B%5Clvert+%7B%2B%7D+%5Crangle%7D+%2Bw_%7B-%7D+%7B%5Clangle+%7B-%7D+%5Crvert%7D+S+%7B%5Clvert+%7B-%7D+%5Crangle%7D+%5C%5C+%26%3D+%5Cfrac%7B%5Chbar%7D%7B2%7D%28+w_%7B%2B%7D+-w_%7B-%7D+%29+%5C%5C+%26%3D+%5Cfrac%7B%5Chbar%7D%7B2%7D%28+w_%7B%2B%7D+-%281+-+w_%7B%2B%7D%29+%29+%5C%5C+%26%3D+%5Chbar+w_%7B%2B%7D+-+%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7B%7B2%7D%7D%5Cend%7Baligned%7D+&bg=fafcff&fg=2a2a2a&s=0&c=20201002)

This gives us

![\begin{aligned}w_{+} = \frac{1}{{\hbar}} [S] + \frac{1}{{2}}\end{aligned}](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cbegin%7Baligned%7Dw_%7B%2B%7D+%3D+%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7B%7B%5Chbar%7D%7D+%5BS%5D+%2B+%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7B%7B2%7D%7D%5Cend%7Baligned%7D+&bg=fafcff&fg=2a2a2a&s=0&c=20201002)

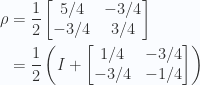

and our density matrix becomes

![\begin{aligned}\rho &=\frac{1}{{2}} ( {\lvert {+} \rangle}{\langle {+} \rvert} +{\lvert {-} \rangle}{\langle {-} \rvert} )+\frac{1}{{\hbar}} [S] ({\lvert {+} \rangle}{\langle {+} \rvert} -{\lvert {+} \rangle}{\langle {+} \rvert}) \\ &=\frac{1}{{2}} I+\frac{1}{{\hbar}} [S] ({\lvert {+} \rangle}{\langle {+} \rvert} -{\lvert {+} \rangle}{\langle {+} \rvert}) \\ \end{aligned}](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cbegin%7Baligned%7D%5Crho+%26%3D%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7B%7B2%7D%7D+%28+%7B%5Clvert+%7B%2B%7D+%5Crangle%7D%7B%5Clangle+%7B%2B%7D+%5Crvert%7D+%2B%7B%5Clvert+%7B-%7D+%5Crangle%7D%7B%5Clangle+%7B-%7D+%5Crvert%7D+%29%2B%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7B%7B%5Chbar%7D%7D+%5BS%5D+%28%7B%5Clvert+%7B%2B%7D+%5Crangle%7D%7B%5Clangle+%7B%2B%7D+%5Crvert%7D+-%7B%5Clvert+%7B%2B%7D+%5Crangle%7D%7B%5Clangle+%7B%2B%7D+%5Crvert%7D%29+%5C%5C+%26%3D%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7B%7B2%7D%7D+I%2B%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7B%7B%5Chbar%7D%7D+%5BS%5D+%28%7B%5Clvert+%7B%2B%7D+%5Crangle%7D%7B%5Clangle+%7B%2B%7D+%5Crvert%7D+-%7B%5Clvert+%7B%2B%7D+%5Crangle%7D%7B%5Clangle+%7B%2B%7D+%5Crvert%7D%29+%5C%5C+%5Cend%7Baligned%7D+&bg=fafcff&fg=2a2a2a&s=0&c=20201002)

Utilizing

We can easily find

So we can write the density matrix in terms of any of the ensemble averages as

![\begin{aligned}\rho =\frac{1}{{2}} I+\frac{1}{{\hbar}} [S_i] \sigma_i=\frac{1}{{2}} (I + [\sigma_i] \sigma_i )\end{aligned}](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cbegin%7Baligned%7D%5Crho+%3D%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7B%7B2%7D%7D+I%2B%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7B%7B%5Chbar%7D%7D+%5BS_i%5D+%5Csigma_i%3D%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7B%7B2%7D%7D+%28I+%2B+%5B%5Csigma_i%5D+%5Csigma_i+%29%5Cend%7Baligned%7D+&bg=fafcff&fg=2a2a2a&s=0&c=20201002)

Alternatively, defining ![\mathbf{P}_i = [\sigma_i] \mathbf{e}_i](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathbf%7BP%7D_i+%3D+%5B%5Csigma_i%5D+%5Cmathbf%7Be%7D_i&bg=fafcff&fg=2a2a2a&s=0&c=20201002) , for any of the directions

, for any of the directions  we can write

we can write

In equation (5.109) we had a similar result in terms of the polarization vector  , and the individual weights

, and the individual weights  , and

, and  , but we see here that this

, but we see here that this  factor can be written exclusively in terms of the ensemble average. Actually, this is also a result in the text, down in (5.113), but we see it here in a more concrete form having picked specific spin directions.

factor can be written exclusively in terms of the ensemble average. Actually, this is also a result in the text, down in (5.113), but we see it here in a more concrete form having picked specific spin directions.

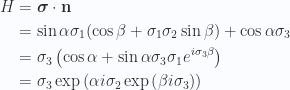

Problem 6.

Statement.

If a Hamiltonian is given by  where

where  , determine the time evolution operator as a 2 x 2 matrix. If a state at

, determine the time evolution operator as a 2 x 2 matrix. If a state at  is given by

is given by

then obtain  .

.

Solution.

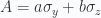

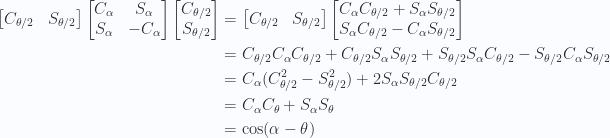

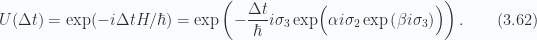

Before diving into the meat of the problem, observe that a tidy factorization of the Hamiltonian is possible as a composition of rotations. That is

So we have for the time evolution operator

Does this really help? I guess not, but it is nice and tidy.

Returning to the specifics of the problem, we note that squaring the Hamiltonian produces the identity matrix

This allows us to exponentiate  by inspection utilizing

by inspection utilizing

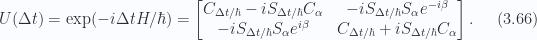

Writing  , and

, and  , we have

, we have

and thus

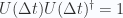

Note that as a sanity check we can calculate that  as expected.

as expected.

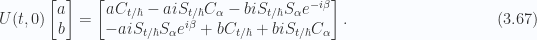

Now for  , we have

, we have

It doesn’t seem terribly illuminating to multiply this all out, but we can factor the results slightly to tidy it up. That gives us

Problem 7.

Statement.

Consider a system of spin  particles in a mixed ensemble containing a mixture of 25\

particles in a mixed ensemble containing a mixture of 25\

Solution.

We have

Giving us

Note that we can also factor the identity out of this for

which is just:

Recall that the ensemble average is related to the trace of the density and operator product

But this, by definition of the ensemble average, is just

We can use this to compute the ensemble averages of the Pauli matrices

We can also find without the explicit matrix multiplication from 3.70

(where to do so we observe that  for

for  and

and  , and

, and  .)

.)

We see that the traces of the density operator and Pauli matrix products act very much like dot products extracting out the ensemble averages, which end up very much like the magnitudes of the projections in each of the directions.

Problem 8.

Statement.

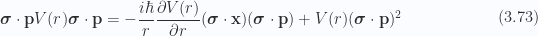

Show that the quantity  , when simplified, has a term proportional to

, when simplified, has a term proportional to  .

.

Solution.

Consider the operation

With  , we have

, we have

which gives us the commutator

![\begin{aligned}\left[{ \boldsymbol{\sigma} \cdot \mathbf{p}},{V(r)}\right]&=- \frac{i \hbar}{r} \frac{\partial {V(r)}}{\partial {r}} (\boldsymbol{\sigma} \cdot \mathbf{x}) \end{aligned} \hspace{\stretch{1}}(3.72)](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cbegin%7Baligned%7D%5Cleft%5B%7B+%5Cboldsymbol%7B%5Csigma%7D+%5Ccdot+%5Cmathbf%7Bp%7D%7D%2C%7BV%28r%29%7D%5Cright%5D%26%3D-+%5Cfrac%7Bi+%5Chbar%7D%7Br%7D+%5Cfrac%7B%5Cpartial+%7BV%28r%29%7D%7D%7B%5Cpartial+%7Br%7D%7D+%28%5Cboldsymbol%7B%5Csigma%7D+%5Ccdot+%5Cmathbf%7Bx%7D%29+%5Cend%7Baligned%7D+%5Chspace%7B%5Cstretch%7B1%7D%7D%283.72%29&bg=fafcff&fg=2a2a2a&s=0&c=20201002)

Insertion into the operator in question we have

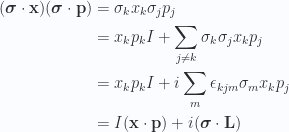

With decomposition of the  into symmetric and antisymmetric components, we should have in the second term our

into symmetric and antisymmetric components, we should have in the second term our

![\begin{aligned}(\boldsymbol{\sigma} \cdot \mathbf{x}) (\boldsymbol{\sigma} \cdot \mathbf{p} )=\frac{1}{{2}} \left\{{\boldsymbol{\sigma} \cdot \mathbf{x}},{\boldsymbol{\sigma} \cdot \mathbf{p}}\right\}+\frac{1}{{2}} \left[{\boldsymbol{\sigma} \cdot \mathbf{x}},{\boldsymbol{\sigma} \cdot \mathbf{p}}\right]\end{aligned} \hspace{\stretch{1}}(3.74)](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cbegin%7Baligned%7D%28%5Cboldsymbol%7B%5Csigma%7D+%5Ccdot+%5Cmathbf%7Bx%7D%29+%28%5Cboldsymbol%7B%5Csigma%7D+%5Ccdot+%5Cmathbf%7Bp%7D+%29%3D%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7B%7B2%7D%7D+%5Cleft%5C%7B%7B%5Cboldsymbol%7B%5Csigma%7D+%5Ccdot+%5Cmathbf%7Bx%7D%7D%2C%7B%5Cboldsymbol%7B%5Csigma%7D+%5Ccdot+%5Cmathbf%7Bp%7D%7D%5Cright%5C%7D%2B%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7B%7B2%7D%7D+%5Cleft%5B%7B%5Cboldsymbol%7B%5Csigma%7D+%5Ccdot+%5Cmathbf%7Bx%7D%7D%2C%7B%5Cboldsymbol%7B%5Csigma%7D+%5Ccdot+%5Cmathbf%7Bp%7D%7D%5Cright%5D%5Cend%7Baligned%7D+%5Chspace%7B%5Cstretch%7B1%7D%7D%283.74%29&bg=fafcff&fg=2a2a2a&s=0&c=20201002)

where we expect ![\boldsymbol{\sigma} \cdot \mathbf{L} \propto \left[{\boldsymbol{\sigma} \cdot \mathbf{x}},{\boldsymbol{\sigma} \cdot \mathbf{p}}\right]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cboldsymbol%7B%5Csigma%7D+%5Ccdot+%5Cmathbf%7BL%7D+%5Cpropto+%5Cleft%5B%7B%5Cboldsymbol%7B%5Csigma%7D+%5Ccdot+%5Cmathbf%7Bx%7D%7D%2C%7B%5Cboldsymbol%7B%5Csigma%7D+%5Ccdot+%5Cmathbf%7Bp%7D%7D%5Cright%5D&bg=fafcff&fg=2a2a2a&s=0&c=20201002) . Alternately in components

. Alternately in components

Problem 9.

Statement.

Solution.

TODO.

References

[1] BR Desai. Quantum mechanics with basic field theory. Cambridge University Press, 2009.